November 3, 2010 — Unarmed, Donald Ward Petersen and the rest of his B-24 crew were given the command to abandon their aircraft, which had been shot by Germans over Innsbruck, Austria. When Petersen landed in the mountains above a small village, a villager found him and led him at gunpoint into the hands of the German Gestapo. The Gestapo took him to Innsbruck and to Luft Stalag IV in what is today Poland, where he was held as a POW for the remaining 11 months of World War II. He became part of the forced march across Poland and Germany that lasted three months in freezing conditions.

On Thursday, Nov. 11 at 11:00 a.m. in the Olpin Union Ballroom, the University of Utah will honor Petersen and ten other Utah veterans at its 13th-annual Veterans Day Commemoration. They will be awarded medallions in a full-dress military ceremony with the university ROTC honor guard and 21-gun salute. To learn more, please visit http://www.veteransday.utah.edu.

To this day, Petersen remembers the sound of the Allied forces as they came toward his prison camp in May, 1945. So scared to leave the bit of food an old woman had given him out of pity, Petersen missed out on the rations distributed by Allied troops. As the German guards dropped their weapons and surrendered, Petersen and the prisoners were pointed in the direction of the Allied front, about ten miles behind them. They had marched 600 miles and endured unthinkable hardships, but – like many from this “greatest generation” – they found the will to march on … toward freedom.

The university has planned a full schedule of events on November 11 to honor all veterans of the United States armed forces. Activities that day are free and open to the public, including the medallion ceremony, a morning panel discussion with military and civilian panelists and a big band performance by the Phoenix Swing Band. Outside of the Union, restored military vehicles will be exhibited and experts will be on hand to discuss their significance to military history.

The honorees are selected by a committee from nominations submitted by friends and family. Six of this year’s honorees served in World War II, two in WWII and Korea, two in Vietnam, and one in all three conflicts.

At 9 a.m., preceding the medallion ceremony, a morning panel discussion entitled “Deployment: From Family to Foxhole” will be held in the Union Theatre. The panel is a 360-degree look at how deployment affects the community-from family members to employers to those deployed-focusing on the 144th Area Support Medical Company (ASMC), which was deployed to Afghanistan in March for a year. Panelists will include Utah National Guard’s Family Support Coordinator, Maj. Annette Barnes; a member of the 144th ASMC; an employer of one of the 144th; and the family of a deployed soldier.

Following the ceremony, at 1:30 p.m. in the Ballroom of the Union, the public is invited to enjoy the big-band sounds of the Phoenix Swing Bandwhose members are local musicians, many of whom are veterans themselves. Later that night at 7:00 p.m., the Utah National Guard 23rd Army Band and Combined Granite School District High School Choir will perform an array of patriotic songs at the Jon M. Huntsman Center. The concert is always free and open to the public. For more information about the evening concert, call 801-432-4407.

2010 HONOREES:

Clayton Bushnell

Clayton Bushnell shipped out to the Philippines as part of the Company K, 3rd Battalion, 381st Regiment, 96th Infantry Division. The unit made an amphibious landing on Okinawa, where Bushnell participated in what has been described the bloodiest battle of the Pacific campaign. Bushnell’s unit was called to scout an “escarpment” that thousands of enemy soldiers occupied. Company K made it up the escarpment and into a village, but Bushnell was wounded. A bullet severed an artery near his heart and an artillery round blew him nearly 30 feet downhill. Bleeding heavily, he was carried back to a holding area, where he was piled with other men who were dead and dying. His next memory was of being prepared for burial. He said something to the startled soldier prepping him, and was taken for medical treatment. Bushnell was flown to Guam, then on to Hawaii. If not for a doctor there who used a new treatment on his badly damaged arm, it would have been amputated.

Paul W. Flandro

Paul W. Flandro was born August 26, 1921. In 1943 he joined the Marines as an artillery officer-a week before graduating from the University of Utah and being commissioned an Army Second Lieutenant. A year later Flandro’s unit, H Battery, 3rd Battalion 10th Marine Regiment, was fighting its way across the South Pacific island of Saipan. They repelled enemy attacks and fired into caves to root out the Japanese, many of whom would choose suicide rather than surrender before the island fell to American forces. Aboard a transport ship, Flandro’s unit was in the middle of a fleet attacked by hundreds of kamikaze pilots. Flandro’s ship was likely spared because the suicide missions were focused on the larger crafts. After the atomic bombs ended the Pacific campaign, Flandro was assigned to help assess the damage in Nagasaki, where the horrific power of the bomb – which bent steel beams to 90 degrees – was evident in the terrible wounds of the casualties.

Douglas Howard

At age 17, Douglas Howard was sent to Calcutta, India with the 191st Combat Engineers and joined the light pontoon bridge company. Howard’s company was tasked with building pontoon bridges over rivers in advance of infantry troops.Howard was wounded in one wrist while working on the Ledo Road, which began in Northern India and passed over mountains and through swamps and thick jungle to connect with the Burma Road. He suffered his wound while attempting to save two buddies who were under intense machine gun fire.He received onsite medical aid, with no anesthetic, from a young medic corporal. His physical wounds healed, but the memories of his friends who didn’t come home still haunt him today. The unit suffered 70 percent casualties from disease and injuries. Howard accepts his award on behalf of his unit buddies who did not return and those who served in the China Burma India Theater, often called the forgotten war.

Wallace Ray Humphreys

In 1943, Wallace Humphreys joined the US Air Force and went to the 71st Bomb Squadron of the 38th Bomb Group, Fifth Air Force, based in Lingayen Gulf, Philippines. On one early-morning mission, he and his crew came under fire. Instead of landing in the dangerous Philippine mountains, they flew three hours away with no radio and only one engine to land on a dirt airstrip without landing gear. During the Vietnam War, Humphreys trained to become a pilot of the H-53 helicopter. Near the Laotian/North Vietnam border, Humphreys went to help another “Jolly Green” crew pick up 18 men stranded on craggy cliffs at 3,000 feet. Under fire, he loaded the first three soldiers and they began to settle toward the cliffs due to extra weight and altitude. He lowered the nose and hoped to miss the rocks. The hoist, with three men aboard, swung into place and his crew dropped two fuel tanks to clear the rocks. It took four trips to get all 18 out.

Theodore G. “Bud” Mahas

In 1943, Bud Mahas joined the U.S. Army Air Corps. He had hoped to become a pilot, but the Army trained him to be a turret gunner on a B-17 bomber. He was assigned to the 8th Air Force, 351st Bomb Group, 511 Bomb Squadron, stationed in England. On each mission, Mahas spent six to eight hours cramped into a three-foot turret on the belly of a B-17, in a fetal-like position, pointing two 50-caliber machine guns between his legs and ready to engage enemy aircraft. During a mission over Berlin, their B-17 was heavily damaged. The heavy flak knocked out two engines and the bomber began to lose altitude. As it traversed the English Channel, the pilot alerted them to “prepare to ditch,” at which point the crew members began praying. Fortunately, the B-17 made it to home base and all survived a crash landing. The repair crew counted 280 flak holes in the plane.

Karl Henry Meyer

On December 27, 1944, Karl Meyer and four other crew members were returning from a combat mission in the China-Burma-India Theater when their B25 erupted into flames and broke in half just as they were about to land. Meyer and the pilot pulled the plane’s engineer from the wreckage minutes before flames ignited the ammunition he was pinned against. Following a two-month recovery from wounds suffered in the crash, Meyer flew 27 more missions, for a total of 55 missions in India and Burma. For saving the life of his crewmember, Meyer received the Soldiers Medal, the highest honor for bravery not involving conflict with the enemy. In the Korean War, Meyer was assigned to the 3rd Bomb Wing, 90th Bomb Squadron, and completed 55 night missions during his 5/12-month tour. Meyer finished out his 27-year career running transport missions to Thule, Greenland, and the Aleutian Islands.

Robert Monson

At 17, Robert Monson enlisted in the Army Air Corps and was called to service upon graduation from high school. He was stationed at an airfield near Spinnazola, Italy, in 1944. They targeted German military stations in the area around Munich and Nuremberg. These areas were heavily defended and flak from anti-aircraft batteries was heavy over every target. On his 15th mission over Austria, Monson had to bail out of his plane and was captured by Germans in the Bavarian Alps. The U.S. and British prisoners were forced to march to Stalag VII-A in freezing rain. The trip took them two to three weeks, during which they had to eat greens picked by the roadside. In the prison camp, POWs endured impossibly crowded conditions, with little to eat, and only a roof for shelter. Monson lost some 50 pounds and was liberated by Patton’s 3rd Army in 1945.

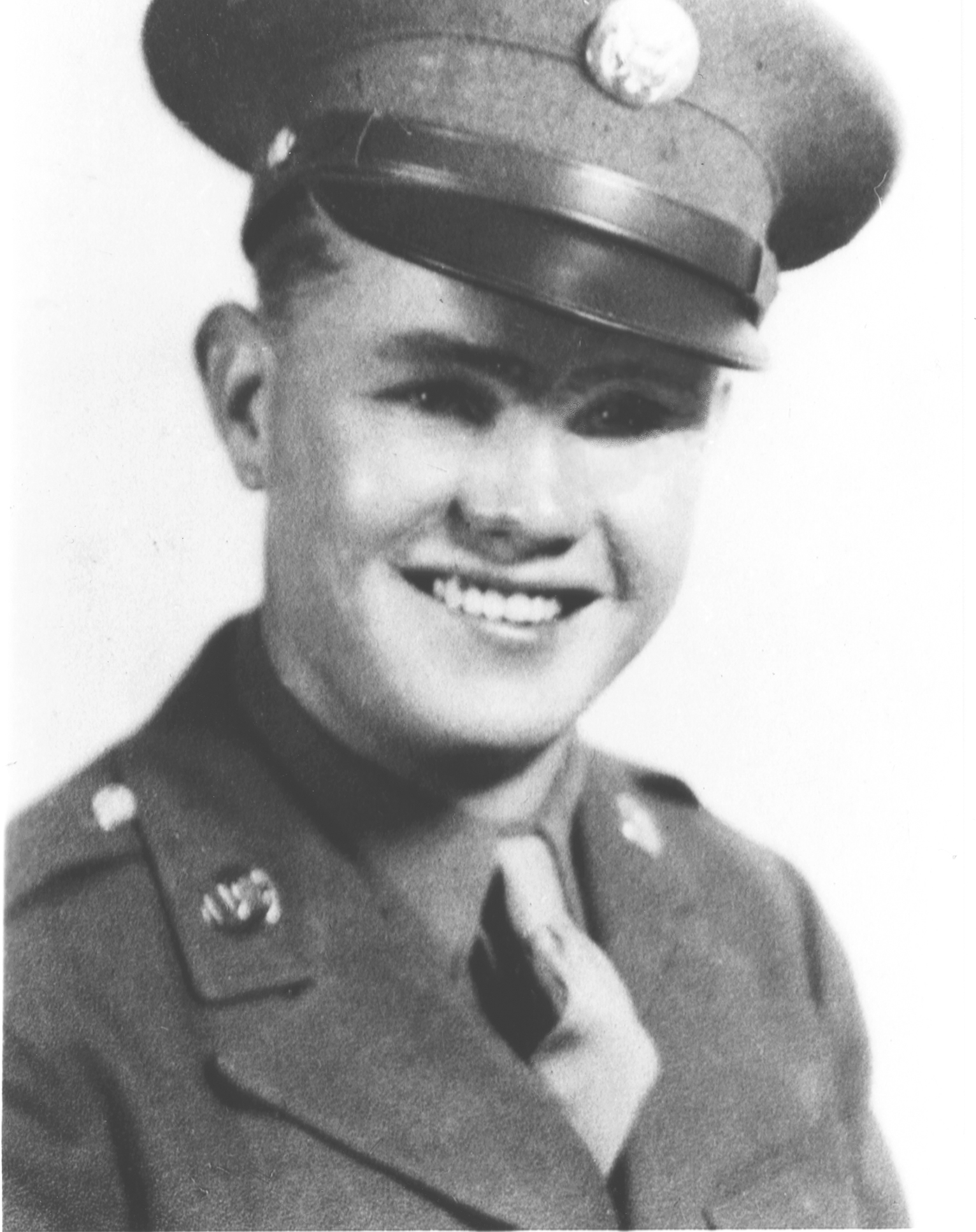

Donald Ward Petersen

In March, 1944, Donald Ward Petersen was deployed to Cerignola, Italy as part of the 15th Air Force, 49th Bombardment wing, 484th Bombardment Group (H), 825th Squadron. On a bombing run to Munich, their group of aircraft was attacked and Petersen was forced to make an emergency landing on top of a mountain in the Austrian Alps. Discovered by locals, he was turned over to the Gestapo, which took him to Luft Stalag IV in present-day Poland, where he was held as a POW for 11 months before being forced to march 600 miles in harsh winter conditions across Poland and Germany. With only a blanket for warmth, Petersen and his fellow POWs slept in fields, drank water from gutters and fought dysentery. After three months of marching, in May 1945, the German guards surrendered to the liberating British troops, leaving the POWs to make their way back to the front lines.

Keith Richardson

Keith Richardson received his pilot’s wings in January, 1944 and was assigned to fly bombing missions from Attu Island to Paramishu Island in northern Japan, a distance of 1,500 miles round-trip. On the last mission, he had to fly just above the swells of the Pacific Ocean to remain below the Japanese radar. On another mission, Richardson had to make an emergency landing on Kamchatka peninsula in the Soviet Union. Because of the Soviet Union’s official neutrality in the war with Japan, Richardson’s crew, and two others, were kept as “internees.” While not official prisoners, they lived primitively and ate poorly. After a month, they were moved near the city of Tashkent. There he spent five grueling months. He lost forty pounds due to malnutrition and lack of adequate clothing in sub-zero weather. Frostbite was a constant threat and took a heavy toll on the men. They were finally taken by truck to Tehran in February 1945, hospitalized, and returned stateside in March, 1945.

Bill “Rock” Rockhill

In 1968, Bill “Rock” Rockhill enlisted in the U.S. Navy with plans of having a desk job as a mechanical draftsman. After boot camp, he learned that position was not available, so he volunteered for combat and was assigned to small boats as part of the U.S. Navy Seals and Underwater Demolition Teams, Coastal Division 11/Underwater Demolition Team #12. Rock arrived in Vietnam in September 1969. His unit intercepted enemy river craft, participated in firefights in hidden bunkers and tunnels, called down air strikes, conducted night combat and jungle fighting, rescued wounded, and laid ambushes for the Vietcong. His specialty was manning a 50 caliber machine gun and 81 millimeter mortar. In 22 months, Rock participated in 100-plus combat missions. When his tour ended in 1971, he had been awarded the Bronze Star for Valor and two Purple Hearts, along with dozens of other commendations.

William Jesse “Bill” Rutledge

William Jesse “Bill” Rutledge always knew he wanted to be a pilot. He entered the Army July 22, 1969 and completed helicopter flight training at Ft. Walters, Texas and Ft. Rucker, Alabama. By late 1969, Rutledge found himself in Vietnam assigned to Bravo Troop 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, 1st Air Cav Division, a unit he volunteered for because he heard that they were “always” in combat. Rutledge logged 1,015 combat hours in Vietnam and Cambodia. In 1971, he earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for “engaging the enemy with rocket and cannon fire with complete disregard for his own personal safety.” He is credited with saving many lives and his actions helped wina major battle. In addition to the Distinguished Flying Cross, Rutledge was also awarded two Bronze Stars, an Air Medal, and the Army Commendation Medal, both with the “v” for valor device.